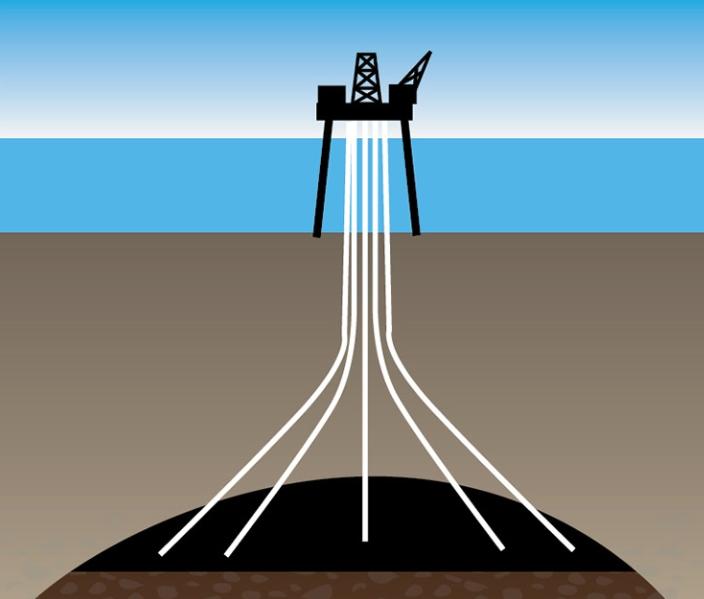

When we picture an offshore oil rig, we often think of the towering structure above the waves—a testament to human engineering. But beneath the surface lies a more complex and consequential story: the impact of its construction on the marine ecosystem. The process of building and installing these massive industrial platforms creates a significant underwater disturbance, with effects that are both immediately disruptive and surprisingly long-lasting.

The journey of a new oil rig begins with seismic surveying. To locate oil and gas reserves, ships use airguns to blast powerful sound waves through the water column. These sonic booms are deafening to marine life, particularly to cetaceans like whales and dolphins, who rely on sound for communication, navigation, and finding food. Studies have shown that these surveys can cause hearing loss, displacement from critical habitats, and disruptions to vital behaviors like breeding and feeding.

Once a site is selected, the physical construction begins. The most impactful phase is the installation of the foundation, which often involves pile driving. This process entails hammering massive steel piles into the seabed to anchor the platform. The noise generated is immense, one of the loudest anthropogenic sounds in the ocean. It can be lethal to nearby fish, causing swim bladder ruptures, and can force marine mammals to flee the area, abandoning their territories.

Furthermore, the initial construction stirs up vast plumes of sediment from the seabed. This increased turbidity can smother sensitive benthic (seafloor) organisms like corals, sponges, and shellfish, which form the foundation of the local food web. The sediment in the water column can also clog the gills of fish and filter-feeding organisms, reducing water quality and sunlight penetration, which affects phytoplankton—the primary producers of the ocean.

However, the story doesn't end with disruption. In a fascinating ecological twist, after the rig is installed, the structure itself becomes something entirely different: an artificial reef. The submerged legs and crossbeams provide a hard, complex surface for colonization. Over time, they become encrusted with barnacles, mussels, and corals. This new habitat attracts small fish, which in turn lure larger predators. A thriving, diverse marine community can develop around a rig, often in areas that were previously featureless muddy plains.

This creates a complex conservation dilemma. While the construction phase is undoubtedly harmful to the original ecosystem, the decommissioned rigs have become valuable marine habitats. The debate now centers on whether "rigs-to-reefs" programs, where old structures are toppled and left in place, provide a net ecological benefit.

The key takeaway is that offshore construction is a double-edged sword. The initial acoustic and physical disturbances are severe and must be mitigated through careful planning, quieter technologies, and seasonal restrictions to avoid sensitive periods for wildlife. Understanding this full lifecycle—from disruptive beginning to artificial reef ending—is crucial for making more informed decisions about our energy infrastructure and its place in the marine world.